Read Part I here.

Transfer Rules from Juvenile to Criminal Court

Despite the establishment of more than 3,000 juvenile tribunals and an Office of the Juvenile Court by the Supreme People's Court there remains to be no unified system of juvenile courts in China. The transfer of serious cases involving juveniles to criminal courts in the US might become an issue in China if a more robust Chinese juvenile justice system arises to address the recent spate of violence among very young offenders. In the early 2000s, US juvenile judges began re-establishing their authority to decide whether to transfer youth in conflict with the law from juvenile court to the criminal court and corrections system. Transfer and waiver of juvenile court jurisdiction is frequently used in cases involving serious crimes by offenders aged 16 and younger.

The 1966 US Supreme Court opinion in Kent v. United States lists eight factors that a juvenile court should consider in determining whether to transfer a case. The factors include the seriousness of the offense, whether the crime was against person or property, the juvenile’s background, and likelihood of rehabilitation. However, in the decades immediately following the Kent decision many states enacted laws to bypass these factors, allowing prosecutors—instead of judges—to decide whether to transfer juveniles. (Some states even allow for automatic transfer.) The states that allow prosecutors instead of judges to file juvenile cases in criminal court, as of the end of 2011, are listed in Chart 2.

Chart 2. States Allowing Prosecutors to File Juvenile Cases in Criminal Court.

Chart source: OJJDP

Several recent laws—many passed during the November elections—re-invigorate judges’ authority to make transfer decisions and rely on factors like those pronounced in Kent. In California, prosecutors were previously allowed to file juvenile cases directly in adult criminal court if they determined that the crime was not appropriate for the juvenile system. But in November, California voters approved Proposition 57, which eliminates direct filing and requires juvenile court judges to determine whether a juvenile will be tried as an adult. The California law also speeds up parole consideration for non-violent felons. In Nevada, new state laws provide that juvenile courts should have exclusive jurisdiction over anyone younger than 16 who is charged with serious crimes like attempted murder; previously, those youths would have been tried in criminal court.

Similar changes have also occurred in other parts of the country: at the age of 12, Paul Gingerich became the youngest person sentenced in adult court in Indiana history, sparking outrage from child welfare advocates. The outrage over Gingerich’s transfer to criminal court likely spurred legal changes that now allow Indiana judges to re-sentence juveniles previously transferred and sentenced to prison terms. With the population of juvenile girls rising, gender also might become a factor for judges to consider during transfer proceedings. As prison policy and practice were designed for adult men, juvenile girls present unique challenges to legal officials; girls in conflict with the law have historically disproportionately high rates of sexual abuse victimization, contributing to high rates of mental health problems. A recent report indicates that such girls have a high need for services but present a disproportionately low risk to the community.

Confidentiality of Juvenile Records and Court Proceedings

Reducing juvenile recidivism also relies on ensuring youthful offender’s successful reintegration into society, whether by protecting their opportunities to complete education or obtain access to employment. In achieving these goals, it is critical that judicial authorities enhance the confidentiality of court hearings and expunge juvenile court records, however the practice of these two procedures vary among American states.

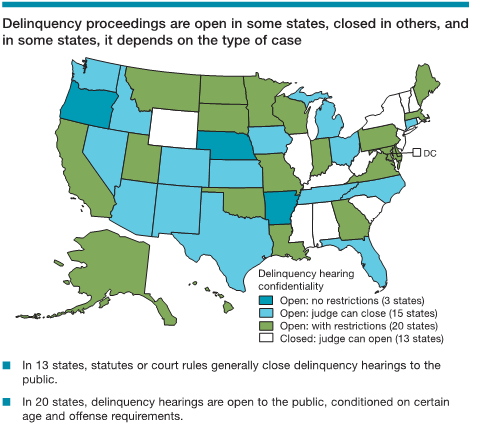

Chart 3. Confidentiality of Juvenile Court Hearings, By State (2011)

Chart Source: OJJDP

The earliest American juvenile courts held public hearings, but by the 1950s, many states restricted public access and media reporting on juvenile court proceedings to prevent juvenile stigma. However in late 1980s, many juvenile courts re-opened their doors to the public amid concerns about rising juvenile crime rates (see Chart 3, above). However, some states continue to close court hearings when a defendant is below a certain age, properly recognizing that confidentiality is an even greater concern when the suspect is very young.

Chart 4: The Sealing of Juvenile Court Records, By State (2011)

Chart Source: OJJDP

Regarding juvenile record sealing, 31 states mandate that juvenile court records cannot be sealed, expunged, or deleted if the court finds that the offender has subsequently been convicted of a felony, misdemeanor, or statutorily-specified juvenile offense (see Chart 4, above). Despite these restrictions, 33 states allow record sealing or expungement in some form, and since 2012, several states have enacted laws to allow juveniles to petition for expungement of records.

Dui Hua has noted in previous collaboration with China’s courts that juvenile offenses can follow a person through life, leaving a lasting impact both on the young offender and on the broader society that collectively bears the repercussions of recidivism. Further policy changes allowing for the appropriate closing of juvenile court proceedings to the public and for juvenile record sealing could prove valuable to US and Chinese policymakers.

Conclusion

Recent trends in US juvenile justice recognize that American juvenile policy in the 1980s and 1990s was based on several mistaken assumptions about the nature of the adolescent brain and the effectiveness of harsh punishment against juveniles, especially those aged 16 and younger.

Current Chinese juvenile court reformers would do well to avoid the same mistakes made in the US during the 1980s and 1990s.

An important first step would be to acknowledge, in light of recent advancements in adolescent neuroscience, that children are not simply small adults. As retired California Superior Court Judge Leonard Edwards writes, progressive juvenile justice reform requires expanding the role of the juvenile judge, who possesses higher quality and quantity of information relative to police or prosecutors. Hence, judges are in “the best position to determine whether a child should be prosecuted as an adult or retained in juvenile court.” Since the beginning of the 2000s, American judges have dramatically increased the implementation of non-custodial measures, helping to limit the transfer of juvenile offenders from juvenile to criminal court.

From this perspective, limiting juvenile incarceration is a “win-win” for those seeking more humane treatments for juveniles as well as for those most interested in lowering the costs of government programs. The cost effectiveness of reducing juvenile incarceration coupled with a deeper understanding of the adolescent brain and the community-based interventions that elicit favorable responses from juveniles should lead to fewer young people housed in state institutions. Conversely, if juvenile recidivism is allowed to increase, harmful effects will only be more severe as the chances of criminal behavior multiply into adulthood.

The juvenile court policies discussed here are but a small sample of a complex and extensive topic. Please investigate the links above to explore other important juvenile policy issues including: access to counsel, conditions of confinement, and status offenses like truancy—the proper handling of which are critical to the long-term reduction of crime and societal tension.