In Leftist Dissent Under Xi: The Young Leftists Part I, Who Are the Young Leftists?, Dui Hua outlined the rise of a new generation of Chinese leftists and their swift repression by Xi Jinping's Communist Party.

Unlike many other labor protests across China, the protests at Jasic Technology in Shenzhen in the summer of 2018 were unusual because of the role leftist students played. These students made an unprecedented move to intervene in a labor rights dispute by venturing into public space side by side with workers.

In April 2018, welding machinery workers at Jasic Technology attempted to form an independent trade union. The nation’s sole legally-mandated All-China Federation of Trade Unions had been tasked with securing better wages, abolishing punitive fines, and improving working conditions. The Federation failed to achieve these goals, prompting the workers to take action. Several workers were dismissed because of their effort to unionize.

The conflict escalated at the end of July, when over 20 workers and one student were arrested for protesting abusive treatment by police. From July 28 to early August, Shen Mengyu (沈梦雨), Yue Xin (岳昕), and sympathizers from Peking University, Tsinghua University, Nanjing University, and Sun Yat-sen University formed the Jasic Workers Solidarity Support Group. In solidarity with the workers, they began posting articles, open letters, photos, videos of speeches and peaceful demonstrations in front of the Jasic factory on digital media. They raised funds for workers, formed human chains, held banners, and chanted slogans alongside dozens of workers from Jasic and nearby factories.

The student-worker coalition demanded the unconditional release of all detained workers and the punishment of police and mob members accused of beating workers. The Jasic protesters also requested the reinstatement of all previously dismissed workers. In less than a month, this student-worker coalition would be no more.

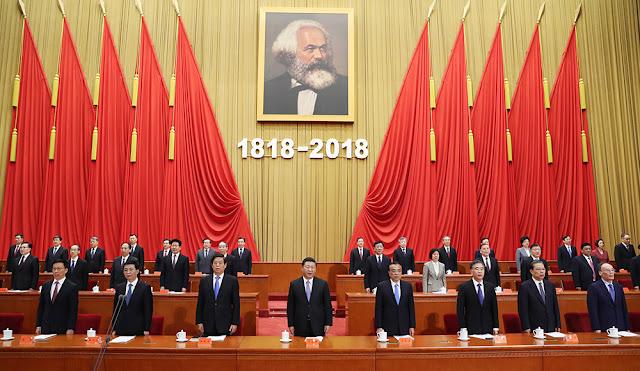

|

On August 10, 2018, members of the Jasic Workers Solidarity Support Group submitted an open letter calling for the Shenzhen Pingshan District Procuratorate to investigate the police’s unlawful detention of workers in Shenzhen. The members (from left to right) were Zheng Yongming (郑永明), Shen Mengyu (沈梦雨), Xu Zhongliang (徐忠良), and Yue Xin (岳昕). Image Credit: @yuexinmutian, via Twitter |

While young Marxists garnered widespread attention for bearing the subsequent brunt of government suppression, “old leftists” also took part in the Jasic protests in a display of solidarity with their young counterparts and the Jasic workers. The South China Morning Post reported that over half of the approximately 80 Jasic supporters who joined the rally on August 6 outside of Yanziling police station in Shenzhen’s Pingshan District were Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members and retired cadres. Many of them held portraits of Chairman Mao as they protested and were active members of Utopia, China’s leading Maoist internet forum.

Other older leftists who were too weak to take to the streets contributed articles for leftist forums or websites. On July 28, as soon as he learned that workers were being detained, Wu Jingtang (吴敬堂) called on all “comrades” to support the Jasic workers in the name of Chairman Mao. Up until his death in early 2019 at the age of 82, Wu was revered for leading thousands of workers to protest the sale of Tonghua Iron and Steel Group in 2009, which they feared would threaten their jobs, and then successfully pressuring several corrupt officials to step down.

After the Jasic protests were crushed in late August, another veteran leftist activist Gu Zhenghua (古正华) wrote in defense of the young Marxists. He openly countered the state media’s accusation that the Jasic protesters were “manipulated by overseas forces.” Gu, who called himself a devoted follower of Chairman Mao and previously worked for the Chinese press, was 90 years old when he penned the article in September 2018.

During the month-long protest, Jasic student activists deliberately eschewed politics. In online posts, they pledged to espouse Marxism or even Maoism by standing with both the CCP and the working class against “local vicious forces.” On August 19, 2018, Yue posted an open letter to Xi, stressing that her activism aligned with Xi’s “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.” Yue attested to the unswerving loyalty of other solidary group members: they were neither plotting a revolution nor pressing for political reforms. They focused solely on helping Jasic workers safeguard their well-deserved labor rights. Jasic supporters young and old wore T-shirts with the slogan “Unity Is Strength,” a patriotic song about the People’s Liberation Army.

Shen Mengyu, wearing a

t-shirt that reads “Unity is Strength,” above left, was taken away by unidentified men on August 11, 2018. Yue Xin and other

members of the Jasic Workers’ Solidarity Support Group, above right, protested

her disappearance on August 13. Image Credit: @wangshi77

and @yuexinmutian, via Twitter

But the tactic of using Marxist or patriotic rhetoric to get the CCP on their side failed. On August 24, anti-riot police raided the students’ apartments in Huizhou and detained approximately 50 people, including Shen Mengyu, Yue Xin, Zheng Yongming (郑永明), and Gu Jiayue (顾佳悦). Most were charged with “picking quarrels and provoking troubles.” The New York Times reported that the activists held hands and sang “L’Internationale” as the police broke through the door.

In response to the police raid on the same day, state-run Xinhua News blamed non-governmental organizations and foreign forces for fanning the Jasic protests. These reports made no mention of the workers’ grievances or their rationale for protesting. Xinhua’s allegation was based on the fact that Fu Changguo (付常国) was an employee of Shenzhen-based Dagongzhe Migrant Workers Center, a local non-governmental organization said to have been “fully funded by an overseas NGO.” Fu is one of more than 50 protesters detained, disappeared, or placed under residential surveillance for participating in the Jasic labor movement.

Aftermath of the Jasic Crackdown

A year after the Jasic crackdown, almost 40 students, workers, and other Jasic supporters with records in Dui Hua’s political database remain in custody or have disappeared and their status remains unclear. In January 2019, about five months after their last public appearance, Shen, Yue, Zheng, and Gu briefly resurfaced in a 30-minute confessional video aired by state security officers to former members of the Jasic Workers’ Solidarity Support Group. In the video, all four pled guilty and admitted to being brainwashed. Shen was reported to have been incited by a “radical organization” to engage in subversive actions to overthrow the CCP.

Observers believe their confessions were staged and scripted because Gu and Shen looked “dull and unresponsive” in the video, a quality observed among rights campaigners, celebrities, and even foreign nationals who have been forced to make confessions on TV since 2014. In many cases, these confessions are made before formal legal proceedings against the confessors have begun. In this sense, the use of public shaming violates the presumption of innocence, and these confessions seem to function more as a show of power rather than any substantial indictment of guilt.

Campus activism has also been quashed. Universities warn students not to participate in protests. Despite its reputation as a wellspring for democracy movements, Peking University ousted leaders of the Marxism Society who were sympathetic to the Jasic workers and replaced them with “loyalists” from the CCP or Communist Youth League in September 2018. In addition to warning students off activism, the university branded the Jasic Workers’ Solidarity Support Group’s activities as “criminal,” in a November 2018 message to all students.

The New Light People’s Development Association at Renmin University, too, is having a hard time recruiting members because migrant workers were pressured by the university and their contractors to leave the organization. Many students also quit after being summoned by university teachers. In November 2018, Nanjing University students were forbidden to register a Marxism reading group in reprisal for writing public letters and delivering speeches supporting the Jasic Workers’ Solidarity Support Group. VOA reported that on November 1 two Nanjing University students were beaten by university guards and thugs on campus while delivering a speech in which they announced their intention to form a Marxist reading association independent of the philosophy department. Their stated aim was to “study the original work of Marxism” and “pay more attention to workers and peasants.” The students were dragged away to an administrative building and later escorted to a police vehicle.

In September 2018, leftist students from various universities and Jasic workers commemorated the 42nd death anniversary of Mao Zedong in his birth province Hunan. Image Credit: Jasic Workers’ Solidarity Support Group’s GitHub

While China continues to sing the praises of Chairman Mao’s legacy, leftist students attempting to commemorate Mao’s 125th birthday in December 2018 were singled out for punishment. At least two Marxist students were taken by police for attempting to attend events related to Mao’s birthday. According to the Jasic Workers Solidarity Group’s Twitter account, Qiu Zhanxuan (邱占萱), who presided over the Peking University Marxism Study Society, was forcibly taken near the university gate by plainclothes police while on his way to attend a memorial he had organized for Mao’s birthday. In a video posted in early 2019, Qiu alleged that he had been strip-searched, slapped, and forced to listen to Xi’s speeches at high volume during an interrogation session in February 2019. Zhan Zhenzhen’s (展振振) whereabouts remain unknown after he was taken away on January 2, 2019 for joining a similar ceremony in Hunan, Mao’s native province.

Several leftists not known to have travelled to Shenzhen to join the Jasic protests have also faced suppression. Leftist scholar Chai Xiaoming (柴晓明) was put under residential surveillance at a designated location for “subversion” in Nanjing on March 21, 2019. Chai was a lecturer at the School of Marxism of Peking University and a part-time editor at the Maoist website Red Reference. One day before he was detained, Chai was involved in the publication of an article by distinguished mainland scholar Jin Canrong (金灿荣), a professor at Renmin University. Jin had called on China to take a different path to modernization.

In August 2018, police from Guangdong raided the Beijing office of Red Reference, confiscating computers and books. Editor Shang Kai (尚恺), a supporter of the Jasic protests, was detained on criminal charges of picking quarrels and provoking troubles. Information concerning Chai, Shang, and the police raid remains sparse.

A year before Xi came to power in 2012, He Bing, a law professor at China University of Political Science and Law, called Bo Xilai’s promotion of “red culture” in Chongqing absurd. “In this absurd time, they encourage you to sing revolutionary songs, but they do not encourage you to wage a revolution.” Almost eight years on, the criticism about the now-disgraced Bo still rings true.

The love for Mao and Marx as a part of modern Chinese patriotism does not translate into love for Xi or his ruling CCP. The “old leftists,” comprised of mostly state-owned enterprise workers and veteran protestors, find themselves increasingly alienated as today’s socialism directly contradicts the system they remember under Mao. Young Marxists also have reasons to feel aggrieved: the motherland they have been taught to love is falling short of their romanticized version of Marxism due to pervasive labor problems and a broad range of other socioeconomic issues. The Chinese government not only ignores these issues, it represses any attempt to raise them in the public sphere. In Xi’s China, even calling attention to existing problems either propagated or tolerated by the infrastructure, no matter how local or apolitical, is an offense to be met by everything from legal obfuscation to intimidation to detainment and being disappeared.

From pro-democracy activists to rights lawyers and religious leaders, the CCP has crushed scores of activists who promote any of the seven political “perils” that Xi warned against in his infamous Document No.9. The reliance on the ideas of Marx, Lenin, or Mao to pave the way for Xi’s “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” has made clear the ideological contradictions between the CCP of yesterday and today, which will continue to impact the Party.

Socialism with Chinese characteristics increasingly looks like an unembarrassed capitalist oligarchy, with “Chinese characteristics” as a catchall term to justify the demand for total fealty. Leftist supporters, both young and old, who do not toe Xi’s line face similar or worse fates than those who try to spread democratic ideals such as a multi-party system and judicial independence: the ideology they espouse may be more threatening to the Chinese government than those ideals which can be dismissed as “coming from the West.”