|

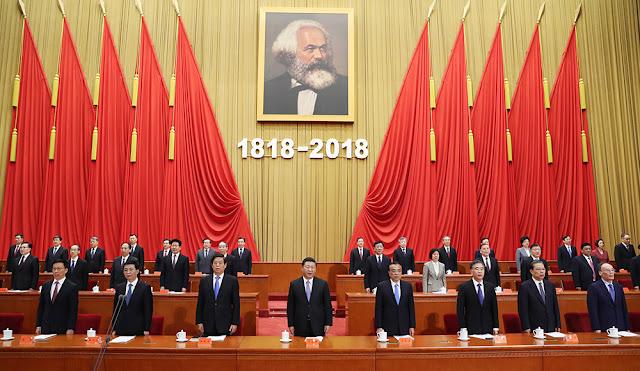

| Xi Jinping leads members of Politburo Standing Committee and other state leaders in celebrating the 200th birthday of Karl Marx in the Great Hall of People on May 5, 2018. Image credit: Xinhuanet |

In May 2018, Xi Jinping led a celebration of the 200th anniversary of Karl Marx’s birthday. During the event, Xi delivered a speech hailing Marx as the greatest thinker of modern times and holding up Marxism as the guiding ideology of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The days before and after Xi’s speech were marked by numerous celebratory events, including the placement of a golden Marx statue in Xi’s hometown.

Just months later, the CCP would engage in a crackdown on leftist supporters who not only shared the same ideological bedrock as the CCP but were actively working to apply Marxism at the local level. The tactics used by the party may not surprise those familiar with the CCP’s handling of any dissent regardless of political ideology. However, the stark contrast between the tone struck by Xi in May and the party’s blatant rejection of those same ideals when carried out by its citizenry served as another reminder of the CCP’s intolerance for dissent, even that which seeks to bring local standards in line with the government’s stated values.

This is the first entry in a two-part post that examines dissent among the ideological left in China. In October 2019, Dui Hua examined the grievances of the “old leftists,” including their efforts to form political parties. Dui Hua has also chronicled leftist subversion in China from 1980-2013. This post turns to a young generation of Marxists who emerged more recently and quickly faced repression in Xi’s China. The second part of this post, which will be released shortly, discusses the young leftists’ roles in the 2018 Jasic workers’ protests, as well as the consequences they faced after the government crackdown.

The emergence of young leftist dissent, which culminated in the outbreak of workers’ protests at Jasic, a welding company, in the summer of 2018, represents an unlikely challenge for the CCP. Xi is continuing China’s decades-long effort to instill the political ideology of the CCP as the rightful successor to Marxism in the education curriculum. He also widely celebrates his own thoughts on socialism by adding “Chinese characteristics” to Marxism. To ensure loyalty and broaden the appeal of his Sinicized version of Marxism for future generations, Xi’s government launched a mobile app in early 2019 to educate school-aged children about the CCP’s ideological orthodoxy.

Despite escalating political indoctrination among China’s youth, a group of self-declared Marxist students came to prominence under Xi’s rule. Most of them were born in the 1990s and early 2000s with no first-hand experience of Mao’s revolutionary zeal for class struggle. Growing up amid China’s economic boom, these young leftists find that the Marxist ideals trumpeted by the CCP in school do not line up with the realities of the society in which they are living. Rather, they see aggravated ideological contradictions in Xi’s “new era,” including increasing state capitalism and social injustice, especially corruption and a widening wealth gap. At the core of their disillusionment are rampant labor rights abuses, including wages in arrears, long work hours, and unlawful layoffs.

Old leftists have joined these young dissenters and harnessed social activism when their interests conflict with government policies. Having grown up in Mao’s China without the benefit of formal Marxist education, their activism is rooted in what they perceive as the tainting of Mao’s ideals by corruption and capitalist tendencies. In contrast, many young leftists are well educated and motivated by the pursuit of social justice derived from Marxist values of equality. These young leftists come from diverse backgrounds, but they began their activism at universities with the formation of various Marxism-Leninism or Mao Zedong Thought discussion groups. In an unprecedented move, this activism would expand beyond the campus as students took their cause into society to support the Jasic workers.

Diverse Backgrounds

The young Marxists who emerged in Xi’s era were students or graduates from various disciplines and social backgrounds. Many of them attended China’s most prestigious universities. One student Marxist from Peking University who spoke to AFP on condition of anonymity said that he read the works of Marx to find ways to help China’s underclass. As the son of migrant farm workers, he believes that he has a sense of social responsibility.

Other activists, like several members of a Marxism study group formed at Guangdong University of Technology in 2017, were born to less well-off families. For instance, chemical engineering student Ye Jianke(叶建科) grew up in Heping, the poorest county in Guangdong. Zheng Yongming (郑永明), a graduate of Nanjing Agricultural University, is a native of Ganzhou, a state-designated poverty city in Jiangxi. Sun Tingting(孙婷婷), a Chinese medicine graduate from Nanjing University, similarly grew up in a poor family in Jiangsu. In November 2017, the study group members took part in a group session and were detained for “gathering a crowd to disturb social order.” Afterwards, Sun released a public letter in which she described the difficulty of paying her legal fees.

If the well-to-do backgrounds of some students made for unlikely Marxists, it did not deter the students’ convictions. For instance, Shen Mengyu (沈梦雨), whose parents are university lecturers, became a student leader who openly supported the Jasic protesters. Shen graduated with a master’s degree in computer science and mathematics from Sun Yat-sen University. Despite a family background and educational qualifications pointing to a bright future, Shen chose to work in a car factory in Guangzhou after graduation to experience life as a proletarian. In an interview with Asia Weekly (paywall), Shen said she did not consider herself a Marxist until she attended graduate school and learned about labor issues by attending talks and following leftist websites online.

Another notable figure, Yue Xin (岳昕), was born to a typical middle-class family. Her family has an apartment in Beijing, and she had a materially trouble-free life. In a now-censored essay about social injustice and inequality published online, Yue expressed guilt for her privileged upbringing, something not afforded to many ordinary Chinese people. Yue became interested in workers’ rights in 2016 when she visited Jakarta as part of a language exchange from Peking University. Prior to her trip, she believed in constitutional democracy. Seeing that the Indonesian political system failed to improve the lives of Indonesian workers who continued to suffer capitalist exploitation, she began to follow labor issues in China more closely upon her return to China in 2017. These views led her to join various campus activities to promote workers’ rights.

Leftist Campus Activism

University students did not appear particularly vocal about labor issues, even after a spate of suicides at Foxconn starting in 2010 and other labor protests that rocked the manufacturing hub of Guangdong. Although many students likely experienced mistreatment while working to support themselves, there were no known collective student efforts to improve workers’ conditions until around 2014.

That year, over 200 sanitation workers in Guangzhou University Town launched a two-week strike to seek severance pay and assurances that the new employer assuming the regional cleaning contract would continue to employ the workers. The striking workers received help from many of the area’s 200,000 students. These students signed an open letter supporting the strike, raised funds, and even brought food and water for the workers. Nevertheless, except for Shen Mengyu, who conducted on-site research about the strike, few students identified as Marxists.

These efforts led to improvements in working conditions, including safer and more hygienic workplaces as well as better-defined work hours and duties. This success also sparked an interest among leftist student groups to improve the treatment of “campus proletarians” like cooks, construction workers, and janitors. In November 2018, Inkstone, a subsidiary of the South China Morning Post, wrote of several Marxist student groups in Jiangsu and Beijing. At Nanjing University, students from Marxist labor rights groups sympathetic to campus workers took up canteen work and organized square dance events. The New Light People’s Development Association at Renmin University supported migrant workers by organizing free clinics, night schools, and dance parties. Only months later, these groups would be suppressed by government action.

Perhaps the best-known student group is the Peking University Marxism Study Society, which was founded in 2000. In late 2015, the society released a report detailing inadequate labor protections for the university’s maintenance staff, including unlawful pay cuts, insufficient social security coverage, and abhorrent living conditions. The report, based on responses from 100 interviewees on campus, urged the university management to act to improve working conditions in accordance with Chinese law.

A follow-up survey conducted in 2017 by Zhan Zhenzhen(展振振) indicated that the university had made no substantive improvements to staff conditions. Perhaps recognizing the risk in making overt criticism, Zhan’s May 2018 report avoided naming and shaming, instead calling on university management to ensure the protection of basic workers’ rights. Although Zhan did not face any disciplinary action for his survey, Peking University warned workers not to cooperate with him lest they be laid off.

While only a small minority of students are devoted to left-wing campus activism, the CCP fears a student-worker coalition that highlights labor rights and broader socio-economic inequalities. The CCP believes such criticisms undermine its vested interests in the increasingly capitalist markets. When the party believes a line has been crossed, it has not hesitated to crack down on leftist student groups, using a variety of methods including coercive measures. Zhang Yunfan (张云帆) was among the first students to have his leftist activism met with such resistance.

A former member of the Peking University Marxism Study Society, Zhang started working in Guangzhou University Town after graduating from Peking University with a major in philosophy in 2016. In 2017, Zhang organized Marxism reading groups at Guangdong University of Technology for like-minded students and graduates. Three of the activists mentioned in this article—Sun Tingting, Ye Jianke, and Zheng Yongmin—were members. In addition to labor rights, Zhang’s reading groups were keen to discuss current affairs, even “June Fourth.”

After a group session on November 15, 2017, Zhang, Ye, and a few other members were initially charged with “illegal business activity” but later detained for “gathering a crowd to disturb social order.” A month later, Zhang and Ye were placed under residential surveillance at a designated location and released on December 29, 2017. Sun and Zheng were also detained in early December and released on bail within a month.

While the Marxist students shared similar passions to improve workers’ rights, some of them expanded their focus to explore women’s rights. Marxist student Yue Xin emerged as a critical voice in China’s #MeToo movement, which began in January 2018. She helped trigger a public reckoning when she began investigating an alleged rape that occurred almost 20 years ago and possibly led to the suicide of a Peking University student in 1998. In April 2018, Yue and other students requested that police disclose information about the investigation of a former literature professor who is believed to have raped the student who committed suicide and coerced other students into sexual relationships. In an open letter Yue published on April 23, 2018, she recounted intimidation by Peking University. The university said that she would not be able to matriculate unless she deleted all related information from her electronic devices.

Many politically engaged students, including those profiled here, reached an important level of commitment with their involvement in the Jasic labor protests of summer 2018. The next post tells their story.