|

China’s anti-cult propaganda likens Falun Gong and Almighty

God to drugs, superstition, and pseudoscience. Image credit: The

Paper

|

A cult is a social group characterized by its unconventional, sometimes controversial religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs. In the United States, mainstream culture and religious leaders consider violent acts such as murder, suicide, and bodily harm as important factors when designating a social group as a cult. Most liberal democracies do not have legislation against cults because any attempt to do so is believed to run counter to freedom of religion enshrined in their constitutions. In China, however, a group can be designated as a cult because its politics and potential to mobilize people are considered threats to Communist Party rule.

Since coming into force in 1997, Article 300 of the Criminal Law—“using or organizing a cult to undermine implementation of the law”—has frequently been used to criminalize non-mainstream religious groups. Observers have long viewed religious persecution as being widespread in China, but they have been unable to quantify the precise extent of the crackdown because reliable figures are not available.

Published by China’s Supreme People’s Court at the end of 2018, Records of People’s Courts Historical Judicial Statistics: 1949-2016 contains extensive information on trials of Article 300 offenses, including statistical breakdowns of sentencing, gender, and defendants’ occupation. These statistics have revealed that over 23,000 cult cases were accepted and over 40,000 people were tried during an 18-year period beginning in 1998.

This is the latest article in a series based on Dui Hua’s research into Records of People’s Courts Historical Judicial Statistics: 1949-2016. Previous posts have explored the decline in juvenile convictions, Hong Kong-related cases, and Taiwan-related cases.

What were the cult cases?

The Criminal Law does not provide an explicit and detailed definition of cult organizations. Back in 1995, the Central Committee, State Council, and Ministry of Public Security identified 14 religious groups (12 Christian and two seemingly Buddhist) as cult organizations. In 2014, the China Anti-Cult Association compiled another list of 20 cult organizations (16 Christian, three quasi-Buddhist, and one qigong). These lists are not exhaustive because local authorities across China have exercised broad discretion to designate numerous religious groups as “cults” even though they have not been named on the aforementioned cult lists.

What were the cult cases?

The Criminal Law does not provide an explicit and detailed definition of cult organizations. Back in 1995, the Central Committee, State Council, and Ministry of Public Security identified 14 religious groups (12 Christian and two seemingly Buddhist) as cult organizations. In 2014, the China Anti-Cult Association compiled another list of 20 cult organizations (16 Christian, three quasi-Buddhist, and one qigong). These lists are not exhaustive because local authorities across China have exercised broad discretion to designate numerous religious groups as “cults” even though they have not been named on the aforementioned cult lists.

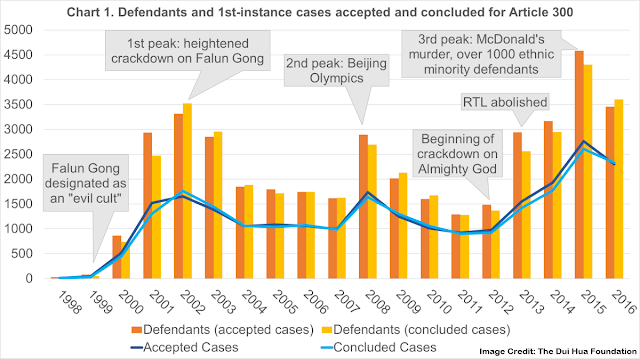

Replacing the former religious crime of “organizing or using a sect or feudal superstition to carry out counterrevolution activities” in 1997, Article 300 began to be used extensively after the Chinese government designated Falun Gong as an “evil cult” in 1999. Before the nationwide repression began, tens of thousands of practitioners could be seen meditating in parks and public squares all over China. Chinese courts began filing the bulk of cult cases a year after Falun Gong was outlawed. The number of people brought to trial skyrocketed from 864 in 2000 to almost 3,000 in 2001. The country recorded its first peak of cult cases in 2002; 3,315 people were brought to first-instance trials.

The second peak took place in 2008; the reasons are not entirely clear. It could be that China ratcheted up stability maintenance in the run up to the Olympics in Beijing. Falun Gong practitioners joined forces with international activists to boycott the Olympic torch relay over China’s extensive human rights violations. Chinese state media called Falun Gong one of the three forces seeking to sabotage the Olympics alongside the East Turkestan and Tibetan independence movements.

The court statistics do not fully reflect the extent of the cult crackdown because they omit a large but unknown number of people whose personal liberties were deprived without any legal procedure. Among these measures are people who are placed in “legal education classes,” which have been used in China for two decades. This measure provides local authorities with a highly flexible means of dealing with individuals who engage in behavior that is viewed as socially disruptive but does not meet the criteria for criminal prosecution or public-order punishment.

The court

statistics also exclude tens of thousands of cult offenders who were sent to

re-education through labor (RTL) camps. Under RTL, individuals could be detained and

subjected to forced labor for up to three years, extendable for another year, for the

vaguely defined conduct of “disrupting social order” on the

decision of the public security organs alone. During the 2009 China session

of the UN Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review, the Chinese government confirmed the existence of 320 RTL

facilities with approximately 190,000 inmates, down from 500,000 inmates in 310

RTL facilities in 2005. At the end of 2012, the Ministry of

Justice claimed that the number of RTL inmates further decreased to 50,000 from

across 351 RTL facilities nationwide.

Despite these limitations, the statistics offer a glimpse of how China invoked its criminal justice process to crack down on religion. The surge of cult cases in 2013 warranted particular attention. Compared to 2012, the number of people who stood trial in 2013 doubled to 2,942. There were two main reasons:

- RTL was abolished in 2013. Cult offenders who were previously sent to RTL are now more likely to face imprisonment sentences.

People in Gansu Province on December 11, 2012 carry a banner warning that Almighty God is coming to save believers and destroy the people and nations that resist. Image credit: Global Times

- China’s sweeping clampdown on Almighty God began in late December 2012. Identified by the Chinese government as a cult organization in 1995, the quasi-Christian group claims that Jesus was reincarnated as a Chinese woman and calls on members to slay the Chinese Communist Party, which they call the “great red dragon.” It joined the chorus of voices spreading rumors of an impending apocalypse, which predicted that the sun would cease to shine and electricity would stop working for three days beginning on December 21, 2012. Prior to the “doomsday,” group members spread the rumors at public venues and by going door-to-door, and they held demonstrations across China which were put down with force.The Chinese press had published very little about Almighty God before 2012, but the demonstrations in that year became the catalyst for China’s propaganda offensive against the sect. Just ahead of the “doomsday,” public security detained 1,300 Almighty God members across 16 provinces, with the majority of them in Qinghai and Guizhou. In 2014, China Daily reported the arrests of another batch of 800 Almighty God members in Ningxia over the previous two years.

The highest peak of cult cases occurred in 2015: 2,764 cases and 4,582 defendants. This peak coincided with the amendment to the Criminal Law which turned Article 300 into a crime with the possibility of life in prison (up from a fixed-term imprisonment sentence of 15 years). In that year, China intensified its propaganda offensive against Almighty God and sentenced two members who allegedly killed a woman in a McDonald’s restaurant to death.

|

|

Dui Hua’s research into online judgments also uncovered cult cases concerning lesser-known unconventional religious groups, including the Three Grades of Servants (三班仆人), Society of Disciples (门徒会), Spirit Sect (灵灵教), Blood of the Holy Spirit (血水圣灵), Lord God Sect (主神教), Full Scope Church (全范围教会), Shouters (呼喊派), and the quasi-Buddhist group Guanyin Famen (观音法门). However, Falun Gong and Almighty God continue to account for the majority of cult cases. Violence is rarely involved in cases involving these organizations.

Over one-third were women

From 2010-2016, women accounted for five to seven percent of defendants in all criminal cases. However, they are disproportionately represented in cult cases tried. The court records indicated that women made up 41 percent of all the 28,497 cult defendants during the 18-year period. In the 2000s, the number of female defendants ranged from 400 to 800 each year, but it doubled in just one year after the state crackdown on Almighty God commenced in December 2012. About 2,600 women stood trial within two years since 2015.

China’s anti-cult propaganda says that women in cult cases are typically middle aged and “left-behind” by husbands (留守妇女) who migrated from rural regions to cities for employment or to conduct business for an extended period. It often makes sexist claims that women are “weak-willed and psychologically vulnerable, with a propensity to succumb to coercion or monetary enticements from cult organizations” because many of them have a low level of education.

Statistics are given about the defendants’ occupational background, but it is unclear how many workers, farmers, and other occupations were women. The statistics indicated that 35 percent of all cult defendants were farmers or migrant workers, and slightly less than one-third were unemployed. Only 7.5 percent of all the defendants were classified as employed or laid-off workers, and another 7.5 percent were retired.

Although China’s anti-cult propaganda tends to describe women as passive victims in cult cases, they are known to have taken a leading role in several religious groups outlawed by the Chinese government. For instance, Guanyin Famen (观音法门) was founded by Vietnam-born Chinese Shi Qinghai in 1988 and introduced to China around 1992. It appears to be the largest of the three Buddhist-sounding groups banned by China (read The “Cult of Buddha” for a more in-depth discussion). Shi, who is residing overseas, continues to attract members in China despite the state ban that has been in place for almost three decades.

Many China-based Guanyin Famen leaders are women. Although the number of publicized cases has decreased sharply in recent years, Dui Hua continues to uncover new cases related to this sect. In September 2019, a local court in Shaanxi sentenced Guo Huiling (郭会玲) to 18 months’ imprisonment. Guo, a leading member in charge of recruiting members in Baoji, was apprehended by public security while distributing Guanyin Famen pamphlet cards in March 2019. The “cult” books, posters, cassette tapes, and CD-ROMs found by public security in her home became the evidence for conviction.

Women have likewise played a leading role in several other homegrown religious groups which emerged relatively recently in the 2010s. Combining elements of Daoism, Buddhism, Chinese folklore, and superstitious practices, these groups have never been mentioned on the different lists of cults compiled by the Chinese government. Their leaders also received lengthy sentences for Article 300.

|

Zheng Hui, founder of the Milky Way Federation, promoted the use of alien energy to become Buddha.

Image credit: Sohu

|

Among these groups are the Milky Way Federation (银河联邦), which was established in 2012 by Zheng Hui (郑辉). Zheng resigned from her job and created a website dedicated to promoting a belief she learned from a group in Germany, which China views as an apocalyptic religious cult. Zheng combined concepts of Buddhism with her belief that extra-terrestrial beings exist. Proclaiming herself to be the female Gautama Buddha, Zheng intended to awaken humankind in her envisioned “Buddha kingdom.” Her group allegedly had over 4,000 members from across China. In July 2015, Zheng was sentenced to eight years in prison under Article 300 in Nanning, Guangxi.

|

Zhongtian Zhengfa is a Buddhist-sounding religious group co-founded by

self-proclaimed reincarnated mother Buddha Chen Yunxiu. Despite propaganda

presenting women as passive victims in cult cases, Chen has played a leading

role in an organization designated as a cult. Image credit: Sina

Blog

|

Bizarre as it may sound, syncretic religious groups similar to the Milky Way Federation appear to have gained popularity in other provinces. Alongside her husband, Chen Yunxiu (陈云秀) founded Zhongtian Zhengfa (中天正法) in 2010 and called herself the reincarnated mother Buddha, Nüwa (the mother goddess in Chinese mythology), and Saint Mary. Zhang said that conversion to her sect would be the only way to obtain salvation. Zheng was sentenced in Shandong to seven years’ imprisonment for Article 300 in 2018. The court judgment indicated that her group had over 900 members from different provinces.