|

| Haikou Intermediate People's Court in Haikou, Hainan Province, People's Republic of China. Image credit: Anna Frodesiak / CCO |

In China, trials for crimes of endangering state security (ESS) are capable of generating intense, international media scrutiny while also being woefully opaque. In the face of severe degradations in judicial transparency, increasingly scant data—the latest from 2020—suggests that ESS trials have surged in recent years.

In Part I, Dui Hua looked at available statistics for ESS trials, focusing on Tibet—where ESS cases rose sharply in 2020—and Xinjiang, which accounted for the largest percentage of ESS trials of any Chinese region through the mid-2010s. This entry considers the rates of additional trials categorized as “other” in China Statistical Yearbooks (中国统计年鉴): dereliction of military duty, criminal offenses prior to 1997, and ESS trials in Han-majority provinces and Guangdong.

“Other” Trials: ESS, Dereliction of Military Duty, and Cases Before 1997

Table 1. Number of cases and people arrested and indicted for dereliction of military duty, 2012-2018

|

| Source: China Statistical Yearbooks |

Dereliction of military duty typically makes up a negligible number of “other” trials. From 2012-2016, Chinese courts concluded 48 trials of dereliction of military duty, just one percent of “other” trials. China Statistical Yearbooks revealed that only two people were arrested for the crime in 2016, and no single arrest was made from 2017-2020. Additionally, no one was indicted in the three years since 2016. Assuming the same trend of arrest and indictment continues, it is to be expected that only a handful of dereliction of military duty cases had proceeded to trials in the four years since 2017.

“Other” trials also include the little-known category of pre-1997 criminal cases, which concern crimes committed before the revised Criminal Law took effect on October 1, 1997. The

Records of People’s Courts Historical Judicial Statistics: 1949-2016 indicated that nearly 60 percent of “other” trials concerned pre-1997 criminal cases from 2012-2016. In 2012 alone, fifteen years after the 1997 Criminal Law came into force, as many as 995 trials were concluded, accounting for 72 percent of “other” trials in that year. While there is insufficient information to estimate the number of pre-1997 criminal cases in recent years, the number showed signs of abating. In 2016, only 88 trials were concluded, down from 651 and 191 trials in 2014 and 2015, respectively.

Table 2. Number of "other" trials and trials of ESS, dereliction of military duty trials, and pre-1997 criminal cases

|

| *(a) = (b) + (c) + (d); Sources: China Statistical Yearbooks & Records of People’s Courts Historical Judicial Statistics: 1949-2016 |

Among the pre-1997 criminal cases to have been concluded after 1997 are the now-defunct crimes of counterrevolution, with a notable example being Chen Yulin (陈瑜琳). The former employee of Xinhua News Agency was accused of handing over materials, including the Xinhua telephone directory and organization chart, to a British agent embedded in the Hong Kong police force during his tenure in the early 1990s. In 2004, he was sentenced to life imprisonment in Guangzhou. He was convicted not of ESS, but of the counterrevolution crime of espionage in accordance with the 1979 Criminal Law. Chen completed his sentence in August 2020 following multiple sentence reductions granted to him since 2007.

Hooliganism, another crime which no longer exists in the 1997 Criminal Law, was among the cases which could be found under the category of pre-1997 criminal cases before the

mass purge of China Judgements Online in June 2021. China’s Criminal Law imposes no limit on the period of prosecution for cases where the suspect has escaped after a pre-1997 criminal case has been filed by police or the procuratorate, or heard by the courts. Some hooliganism cases concern prisoners who were released on probation but re-sentenced after 1997 for violating parole rules. Courts can also hear a new case and extend sentences for hooliganism prisoners for violating prison regulations. A few prisoners were sentenced to new offenses that were missing in the original hooliganism trials, and thus received sentence extensions.

Han-Majority Provinces & Guangdong

Outside of Tibetan regions and Xinjiang, Dui Hua’s research into provincial statistical yearbooks found that few ESS trials have been concluded in Han-majority provinces. In Chongqing, no ESS trials were held from 2018-2020. Hainan accepted and concluded two ESS trials in 2020, whereas Guizhou only held one ESS trial every year from 2014-2019.

More ESS trials took place in Guangdong, but the figures are far out of proportion given the province’s large population. From 2013-2019, courts in Guangdong concluded 54 ESS trials. Although the numbers in 2020-2021 are not yet available, it is likely that some of the latest ESS trials were closely related to Hong Kong.

In 2018 and 2019, Guangdong authorities arrested a total of 17 people on suspicion of ESS and indicted a total of 30 people on ESS charges. Some of the ESS arrests in Guangdong over the past three years involved Hong Kong’s anti-extradition bill protests. In April 2021,

state-run news media publicized four ESS cases in Guangdong, two of which were Hong Kong-related. In June 2020, a university student from Hong Kong surnamed Yeung was accused of subversion while studying in the mainland. Yeung not only retweeted in support of Hong Kong’s “black-clad mobs,” but also smeared the police force with a stated goal to bring Hong Kong’s model of political resistance to China.

In the second case, a mainland student studying at the University of Hong Kong posted information on social media to support Hong Kong protesters and attack the central government. His messages also included “liberate Hong Kong,” a banned slogan also deemed capable of inciting secession in the former British colony. Detained in June 2020 upon his return to the mainland, the student reportedly wrote a 100,000-word repentance statement in which he vowed not to take part in activity that endangers state security.

More Hong Kong-related ESS arrests were made in Guangdong. In September 2021, news media sources reported that

independent journalist Huang Xueqin (黄雪琴) was placed under residential surveillance at a designated location in Shenzhen. She was formally arrested for inciting subversion the following month. Prior to her arrest, Huang was briefly detained for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” in 2019 after taking part in and publishing writings about the Hong Kong protests. Arrested with Huang in October was her friend Wang Jianbin (王建兵), an education and labor advocate. Wang too was arrested for inciting subversion.

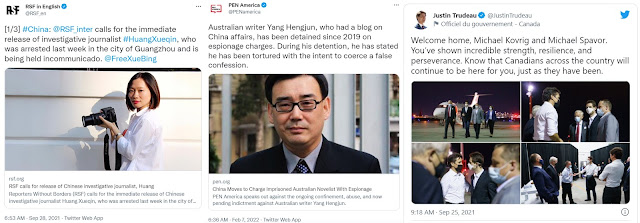

ESS trials have long been criticized for being opaque. A number of these trials were held behind closed doors with citizens, journalists and foreign diplomats shut out, as in the cases of the Canadians

Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig and Australian citizen

Yang Hengjun (杨恒君, aka Yang Jun). The identities, acts, and fates of many more people tried, convicted, and sentenced in ESS cases are not known.

|

| Media attention for recent ESS cases on Twitter (left to right): Reporters Without Borders calls for the release of Huang Xueqin; PEN America calls for the release of Yang Hengjun; Canada’s Prime Minister hails the release of Michaels Kovrig and Spavor. Image credits: RSF in English Twitter account; PEN America Twitter account; Justin Trudeau Twitter account |

In 2021, transparency of ESS cases dipped to a record low. Dui Hua’s Political Prisoner Database has information on 68 individuals who were sentenced in ESS trials of first instance in 2020. With the mass purge of court judgments online, the Chinese government has undone some of its progress in judicial transparency and, in doing so, possibly harmed its own rule of law.